Queen’s University Belfast joins the group of Climate In Situ users

At the beginning of October, DENSsolutions installed a Climate G system at the Queen’s University Belfast, Northern Ireland, UK.

Dr. Miryam Arredondo-Arechavala

Applications

The system will be mainly used by Dr. Miryam Arredondo-Arechavala and her group to study ferroelectrics and other functional materials. Alongside this, it will help accelerate research on ionic liquids performed by the QUILL Research Centre (Queen’s University Belfast’s Ionic Liquid Laboratories) and other catalyst projects at Queen’s University Belfast.

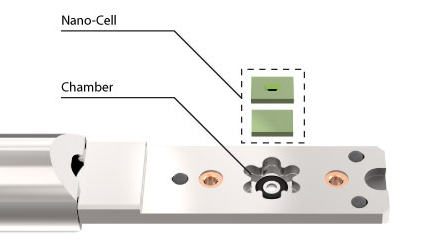

The DENSsolutions Climate holder inserted in the Talos TEM for the first time.

Installation and first experiment

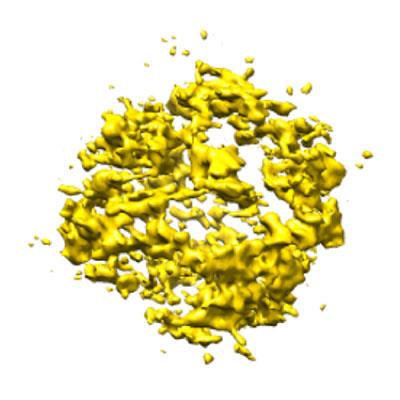

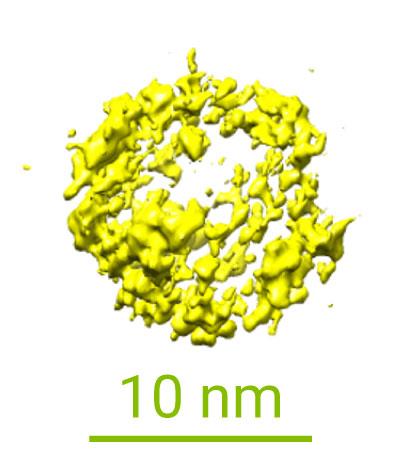

The system was installed in less than two days by our Climate product manager Ronald Marx. After this, Marx provided hands-on training for the new group of users. The team was able to start their first In Situ Gas & Heating experiment using their own sample of Zeolite particles which was dropcasted on to the Climate Nano-Reactor. Seeing the first results created a lot of enthusiasm among the group of principal investigators and their colleagues from the chemistry department.

Learn more about our Climate system:

Discover publications in which our Climate system was used: