Improved insight into catalytic reduction of NOx for industrial processes

In Situ TEM supports the design process of a new nanorod catalyst

Original article by Zhaoxia Ma, Liping Sheng, Xinwei Wang, Wentao Yuan, Shiyuan Chen, Wei Xue, Gaorong Han, Ze Zhang, Hangsheng Yang, Yunhao Lu, and Yong Wang. Published in Advanced Materials, volume 31, issue 42.

Artist impression showing growth of carbon nanotubes via an iron-catalyzed process. © 2019 DENSsolutions All Rights Reserved

There is a big opportunity for the design and development of sustainable catalysts for low-temperature NOx removal in the steel, cement and glass industries. Researchers Dr. Yong Wang et al. from Zhejiang University made a recent breakthrough using critical information obtained by In Situ TEM to design a MnOx/CeO2 nanorod (NR) catalyst with outstanding resistance to SO2 deactivation. Former studies proposed methods which succeeded in temporarily diminishing the influence of SO2 but lost their effectiveness over time. In this study, a dynamic equilibrium was achieved between sulfates formation and decomposition over the CeO2 nanorod surface, resulting in an unchanged NOx reaction rate for 1000 hours.

In Situ TEM study

Up till now, researchers have not been able to see exactly what happens to the CeO2 catalyst particle when exposed to SO2 because SO2 is so corrosive that it would damage the environmental transmission electron microscope (ETEM). Now, thanks to the DENSsolutions Climate in situ TEM Gas and Heating system, scientists can for the first time observe and record this degradation process at the atomic scale. Dr. Wang’s team found out that non-active amorphous cerium sulfates were formed from the reaction between SO2 and CeO2. The cerium sulfates formed a deposit which gradually coated the crystalline surface of the nanorods that was catalytically active.

Video 1. In situ TEM observation of the formation and evolution of cerium sulfate over Ce02 nanorods during treatment in 1000 ppm NO, 1000 ppm SO2, and 10 vol% 02 balanced with Ar at 523K. The two white arrows point to amorphous bumps at the end of Ce02 nanorods.

Video 2. In situ TEM observation of dynamic evolution of cerium sulfates during treatment in 1000 ppm NO, 1000 ppm NH3, and 10 vol% 02 balanced with Ar at 523K. The white dashed circles indicate the amorphous cerium sulfate bumps, which decomposed after the introduction of NH3.

In the first part of the In Situ TEM experiment, the researchers introduced diluted SO2 to study the deactivation behaviour of CeO2. Many obvious bumps were formed on the surface of the CeO2 nanorods (NR); this dynamic formation process can be seen in video 1. After this step, the researchers used their Climate Gas Supply System to switch off the SO2 gas flow to the TEM and switched on the diluted NH3 gas flow. The researchers could then observe the amorphous cerium sulfate bumps to become smaller and finally almost disappear at 523 K. The decomposition of the cerium sulfate bumps can be seen in video 2. This change back to polycrystalline CeO2 can be seen in detail in video 3.

Video 3. In situ TEM observation of dynamic evolution of a single cerium sulfate bump during treatment in 1000 ppm NO, 1000 ppm NH3, and 10 vol% 02 balanced with Ar at 523K. The white arrow points to amorphous cerium sulfates, which retransformed into crystalline Ce02 after the introduction of NH3.

Image 1. DENSsolutions Gas Supply System

The Gas Supply System (image 1) of the Climate G+ gas & heating system can continuously mix (dilute) gas flows from up to 3 sources. The mixing ratios for these 3 gas flows, typically 1 reducing, 1 oxidizing and 1 inert (carrier) gas, can be changed real-time between 0% and 100% according to the requirements of the in situ TEM experiment. This makes it the ideal tool for new discoveries in gas-solid interactions.

“Thanks to the state-of-the-art gas cell system from DENSsolutions, we can simply move the industrial reactions into the TEM and observe what really happens for the catalysts during reactions with atomic resolution at atmospheric pressure. This is the first time we attempted to introduce industrial gases like NH3 and SO2 to the gas cell system. To our surprise, this system was pretty robust and worked perfectly when studying the catalytic reactions involved in SO2 poisoning.”

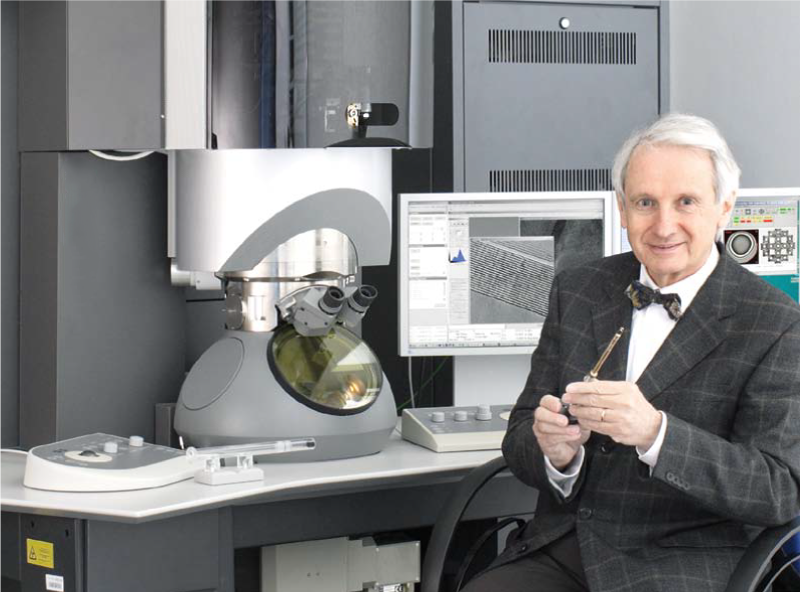

Dr. Yong Wang – Zhejiang University

Learn more about our Climate system and Nano-Reactor:

Discover more publications made possible by our Climate system:

Read the original article: