Membranes made from Nano-droplets have potential in Medical Research

Membranes formed in-lab from nano-droplets could have future use in medicines

LPEM Movie of the in-situ self-assembly experiment. Stabilized and cropped. Ianiro, A. et al. Nat. Chem. (2019)

This experiment has continuously recorded the whole process of how the membrane is formed under a microscope. Before this, scientists had to freeze the final membrane and get a snapshot of one or several moments of the membrane forming. This advance is achieved due to a well controlled liquid environment and can be now set in the microscope thanks to the DENSsolutions Ocean system.

The Experiment

The researchers from the Materials and Interface Chemistry group led by Prof. Nico Sommerdijk formed a membrane from soap-like molecules called amphiphilic molecules, which simply means that they interact with both fats and water. Amphiphilic molecules are good building blocks for membranes as they can be lined up with the water-interacting side facing one way and the lipid-interacting parts facing the other way to form larger structures.

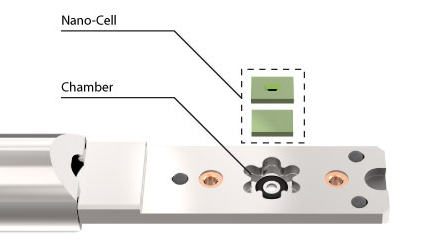

The DENSsolutions Ocean In Situ TEM liquid system was essential in this research. The core of the system consists of a dual chip Nano-Cell that sandwiches two chips together to form a microfluidic compartment.

Step 1. Polymer solvent

Step 2. Air

Step 3. Water

Future Research

Watching how the nanoparticles form and arrange themselves with an electron microscope is a huge step in learning how to manipulate these membranes. The techniques covered in this research will be of interest to scientists working in food science, synthesis chemistry and separation science.

Hanglong Wu, who made a significant contribution to this paper during his PhD period, commented in an interview with DENSsolutions, that the technique “has been extensively used in studying the dynamics and structures of hard materials (for example, metallic nanoparticles) in the aqueous solution in the last decade, but it has been barely employed into soft matter field, mainly due to the inherent high beam sensitivity and low contrast.

The next stage will be fine-tuning how to manipulate the size and shape of the membrane. This research from Eindhoven is an important step in an exciting field.

If you are interested in the equipment we provided for this research, then contact us to see how we can streamline your experiments.

Membranes formed in-lab from nano-droplets could have future use in medicines

LPEM Movie of the in-situ self-assembly experiment. Stabilized and cropped. Ianiro, A. et al. Nat. Chem. (2019)

This experiment has continuously recorded the whole process of how the membrane is formed under a microscope. Before this, scientists had to freeze the final membrane and get a snapshot of one or several moments of the membrane forming. This advance is achieved due to a well controlled liquid environment and can be now set in the microscope thanks to the DENSsolutions Ocean system.

The Experiment

The researchers from the Materials and Interface Chemistry group led by Prof. Nico Sommerdijk formed a membrane from soap-like molecules called amphiphilic molecules, which simply means that they interact with both fats and water. Amphiphilic molecules are good building blocks for membranes as they can be lined up with the water-interacting side facing one way and the lipid-interacting parts facing the other way to form larger structures.

The DENSsolutions Ocean In Situ TEM liquid system was essential in this research. The core of the system consists of a dual chip Nano-Cell that sandwiches two chips together to form a microfluidic compartment.

Step 1. Polymer solvent

Step 2. Air

Step 3. Water

Future Research

Watching how the nanoparticles form and arrange themselves with an electron microscope is a huge step in learning how to manipulate these membranes. The techniques covered in this research will be of interest to scientists working in food science, synthesis chemistry and separation science.

Hanglong Wu, who made a significant contribution to this paper during his PhD period, commented in an interview with DENSsolutions, that the technique “has been extensively used in studying the dynamics and structures of hard materials (for example, metallic nanoparticles) in the aqueous solution in the last decade, but it has been barely employed into soft matter field, mainly due to the inherent high beam sensitivity and low contrast.

“In this Nat. Chem. paper, we actually demonstrate we can probe the soft matter formation with such high contrast. People for sure will start to use the technique in the soft matter field.” – Hanglong Wu

The next stage will be fine-tuning how to manipulate the size and shape of the membrane. This research from Eindhoven is an important step in an exciting field.

If you are interested in the equipment we provided for this research, then contact us to see how we can streamline your experiments.